Creativity

As recent research has found (Chuderski, 2013), working memory strongly correlates with fluid intelligence and reasoning. Therefore, working memory is a key resource for complex cognition.

So how could you improve this powerful and sophisticated, yet resource-hungry and somewhat limited engine? In this article, we offer one powerful way for using your working memory both efficiently and effectively: represent your problem graphically.

People show large improvements in fluid reasoning after learning how to draw diagrams to represent a problem (Nickerson, 2003). Graphical representations store information externally, freeing up working memory resources for other aspects of thinking, serving as the knowledge store. A second advantage is that graphical representations organize knowledge by indexing it spatially, thus reflecting the relationships among the different items of a given problem. For example, if the representation of two items is close in the graphic, it is likely that those items are also close in the problem at hand. Therefore, a spatial arrangement of information allows for interpreting and making inferences of the problem: you could grasp the gist of the problem while seeing how its items interact with the problem. Moreover, when nonvisual information is mapped onto visual variables, patterns often emerge that were not explicitly built in, but which are easily grasped by the graphical representation of the problem (Card, et al., 1999). These representations enable complex reasoning computations to be replaced by simple pattern recognition processes.

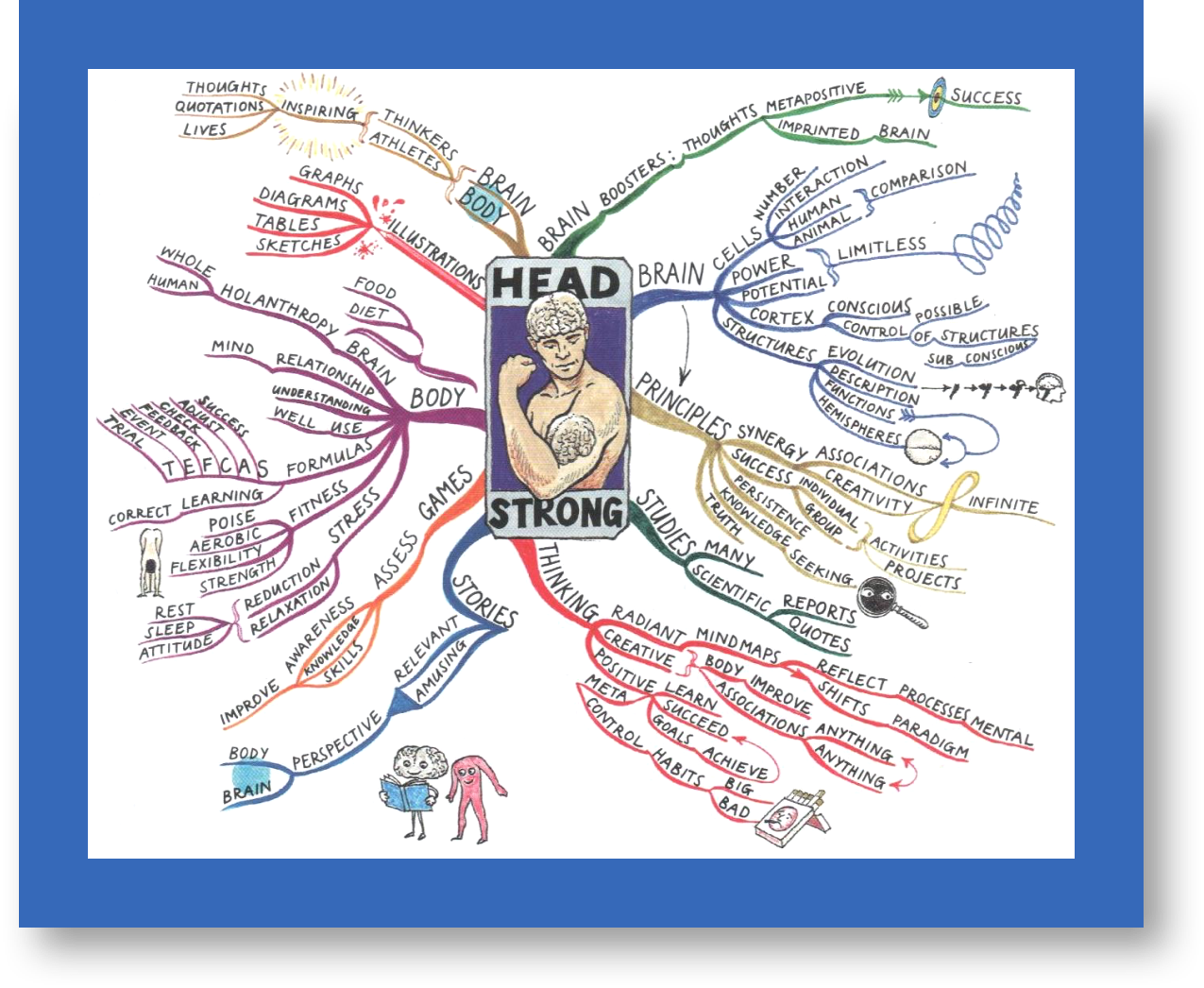

The following Mind Map illustrates how Tony Buzan, the inventor of this methodology, designed his book titled “Head Strong”. The main branches represent the chapters of the book, while the sub-branches encapsulate the key information within the chapters. Notice how Tony uses a combination of images, keywords, color and associations to represent the gist of his 300-page book into a single-page canvas.

Mind Mapping allows people to draw on all aspects of their intellectual and creative abilities simultaneously. The process of creating a Mind Map helps them commit information to memory, enables them to visualize concepts and the way they relate to one another, and enhances creative thinking and problem solving skills. In other words, Mind Maps use the otherwise limited capacities of working memory in a very powerful way.

Several studies have pointed out that people have benefited from increased attention, organized thinking, and a better approach for sharing ideas by adopting this methodology. Deciding the structure of the Mind Map, its layout, its keywords and images, and the overall organization of the information it contains, builds critical thinking abilities, and improves problem solving skills.

By using all thought functions simultaneously, including creative and rational thinking, Mind Maps allow people to expand their overall thinking ability and train themselves to think more robustly in the future. They eliminate the single method of approaching a concept or idea and instead employ multiple thought processes without overtaxing the limited but very sophisticated capacities of our working memory.

References

Buzan, T. & Buzan, B. (1996): The Mind Map Book: How to Use Radiant Thinking to Maximize Your Brain’s Untapped Potential. New York, NY: Plume.

Card, S. K., Mackinlay, J. D., & Shneiderman, B. (1999). Readings in information visualization: using vision to think. Morgan Kaufmann.

Chuderski, A. (2013). When are fluid intelligence and working memory isomorphic and when are they not? Intelligence, 41(4), 244-262.

Conway, A. R., Cowan, N., & Bunting, M. F. (2001). The cocktail party phenomenon revisited: The importance of working memory capacity. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 8(2), 331-335.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63(2), 81.